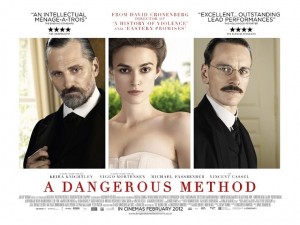

‘The Horror Comes from within Man’: David Cronenberg’s A Dangerous Method

Helena Bassil-Morozow PhD, is a cultural studies theorist and film scholar. This post is a copy of her talk given at the Confederation for Analytical Psychology Conference – A Dangerous Method which was presented on Saturday 11th February 2012.

It does not come as a surprise that the body horror director David Cronenberg chose psychoanalysis as the subject of his latest work. Psychoanalysis must appeal to Cronenberg because it allows him to go back to the roots of violence, sexual deviations and other human demons he has explored in his career to date. Moreover, the subject takes him to the beginning of the twentieth century, when these demons were being seriously analysed for the first time in history. The director is keen to have a closer look at the people who ‘registered’ the ‘death of God’ because they recognised the tragic pervasiveness of evil in humankind. And Cronenberg is particularly keen to pick on Jung because Jung is still clinging to his ‘defences’ – myth, religion and spirituality – all of which the director dismisses. The protagonist of A Dangerous Method is still hoping to ‘revive’ God.

A Dangerous Method is a very typical Cronebergian film in the sense that it explores the director’s pet themes: fragmentation, contamination, institutionalisation of the body and mind, and existential disorientation and confusion. Jung is turned into yet another fragile Cronenberg protagonist who loses the fight with the unconscious (often metaphorically presented in his films as a wound) and ends up being infected by its contents.

The result is rather perplexing. Jung would have had difficulty recognising himself in this rather Freudian interpretation of the origins of psychoanalysis. In a recent interview with Film Quarterly Cronenberg said:

I suppose one of the reasons that I would prefer Freud to Jung is that I think that Freud insisted on the reality of the human body at a time when the body was covered up by many stiff layers of clothing. Freud was saying: no, all of these orifices and fluids and things are of actual significance and importance to the human psyche whether we like it or not. Whereas Jung wanted to sort of flee the body and become a spiritual leader which I think is what happened. He became more like a religious leader than a physician, in my opinion.

(Ratner, 2012: XX)

Being the protagonist in a Cronenberg film usually means being subjected to all kinds of torture and weird transformations, and in no way can Jung the protagonist escape the same destiny. Completely disregarding this ‘religious’ aspect of Jung’s psychology, Cronenberg brings him back to the question of the body; he drags him, kicking and screaming, back to Freud; he rubs his nose in sex, the instincts, fluids, physicality; he makes him witness and accept the dark, uncontrollable, unpredictable side of human sexuality. Sabina Spielrein and Otto Gross become his accomplices in this elaborate torture of the spiritual man who dares to think that sex is not everything and that there is life outside the narrow cage of the body. ‘Sexuality is an area in which we are not fully evolved – the director says in the book of interviews Cronenberg on Cronenberg – culturally, physically or in any other way’ (Rodley, 1996: 65).

The first phase of the trial he invents for Jung consists of taking away Jung’s spirituality and leaving him face to face with the monsters that are human instincts. Religion, Cronenberg implies, is a toy for the deluded; a shield against existential emptiness; a fragile bridge across the void. It is something cowards use in order to avoid the difficulty and responsibility of individual decisions. It is all too easy to attain personal wholeness with myth; to heal the broken psyche of modern man with the promise of God in whatever form; to water the wasteland of modernity with fables. Cronenberg remains sceptical of such methods. His aesthetics calls for a broken psyche – disjointed, cut into pieces, mutilated, torn, tortured, and murdered in a snuff film. The images of disintegration he mercilessly creates throughout his career – the repugnant bodily transformations in The Fly (1986), the gynaecological nightmare of Dead Ringers (1988), the sexual perversions of Crash (1996), the mindless, highly contagious violence in Videodrome (1983) – all go back to the waste land of the western soul. Instead of healing the Cartesian schism, he widens it with his surgical instruments and shows its ugly contents. Like the vagina on Max Renn’s stomach in Videodrome, the schism is eternal, outside of human control, and does not heal. In fact, Keira Knightley’s bodily contortions and hysterical faces belong to the same tradition.

Modern man – Cronenberg implies – is not ‘in search of a soul’. There is no such as thing as a soul in the first place. In the world characterised by existentialist freedom, the tortured free will is exhausted by making constant moral choices in the absence of a higher authority; a bigger organising superstructure. In this the director follows his hero, the trail-blazer, the supreme master of disintegration – William Burroughs, and especially his controversial novel The Naked Lunch. He is also a big fan of the playwright whose talent of rendering the existential emptiness in a dialogue was breathtaking – Samuel Beckett.

The darker aspect of this position is expressed in the film by Otto Gross when se says that the psychotherapist’s job is to make the patient ‘capable of freedom’ (and, in his case, total freedom is so destabilising that it merges with madness). The more positive angle on the issue is taken by Sabina Spielrein who announces to Jung half way through the film that she wants to be a doctor because she aspires to give people their freedom (release them from the prison of their problems – and from the rigid framework of their bodies).

The director says in an interview published in Cronenberg on Cronenberg:

The phrase ‘biological horror’ – often attached to my work – really refers to the fact that my films are very body-conscious. They’re very conscious of physical existence as a living organism, rather than other horror films or science-fiction films which are very technologically oriented, or concerned with the supernatural, and in that sense are very disembodied.

I’ve never been religious in the sense that I felt there was a God, that there was an external structure, universal and cosmic, that was imposed on human beings. I always really did feel – at first not consciously and then quite consciously – that we have created our own universe. Therefore, what is wrong with it also comes from us. That isn’t to say that we make all the rules, just that my worldview is human-centered as opposed to being centered outside humanity. I think this naturally leads you to the feeling that, if you’re dealing with horror, it must also be human-centered. It comes from within man.

(Rodley, 1996: 58)

Cronenberg also wants to show the limitations offered by the body: ‘I am attached to the notion that I am free and that my will determines my own life’ (1996: 144). His latest film confirms his idea that human beings ‘carry the seeds of their own destruction with them, always, and that they can erupt at any time. Because there is no defence against it; there is no escape from it’ (1996: 58). This is reflected by the self-disgust from which Keira Knightley’s character suffers in the film: ‘I am violent, filthy and corrupt. I must never get out of here [the Burghölzli hospital)’.

The next phase of the torture process involves the question of social class. A traditional middle class man who had a perfect childhood, Cronenberg is keen to challenge and dismiss what he sees as the sterility of the middle-class lifestyle. He becomes the trickster, undressing the body and showing all the unsightly scars to his shocked, decent audience. He dissects, he uncovers, he crosses all possible boundaries of good taste and moral behaviour. He says that in films like Shivers (about sexually transmitted parasites that cause uncontrollable sexual desire in the host), he identifies with the devious little creature infecting nice middle class people, and throwing them into the world of completely new, ugly and nasty, experiences, thereby forcing them to change their view about everything (Rodley, 1996: 82). In fact, the director often uses the metaphor of ‘infection’ – diseases, parasites – to show the artificiality of middle class civilizednes and its habit of shoving all the unpleasant and uncomfortable aspects of the body under the carpet. All the while, flesh breaks free, flesh cannot be controlled by ‘systems’, including the code of medical conduct.

Naturally, Cronenberg identifies Jung as a typical bourgeois man trapped in a typical, asexual bourgeois marriage. The director completes his torture by infecting Jung with the demons of sado-masochism, sexual anarchism and madness courtesy of highly contagious transmitters such as Sabina and Otto Gross. Like a cruel scientific experimenter out of his own horror films, he strips Jung of his defences and watches him try and find the way out of the maze of existential emptiness and seemingly unsolvable moral dilemmas. So, how does the nice and clean middle class man Jung bear the torture invented for him by Cronenberg?

Given the deplorable circumstances, Jung fares relatively well. He is listless but heroic, a sort of Harry Potter of psychoanalysis, struggling with the monsters crawling out of the depths of his and his patients’ unconscious. Normally, these dangerous contents are to be released in framed and controlled circumstances such as association tests, and contained within stringent professional boundaries to minimize transference and counter-transference. But eventually the demons he extracts from the depths, and dissects, stage a Frankensteinesque revolt and run away. The dangerous method of the title is kind of sci-fi portal through which they escape. Cronenberg believes in the independence of the flesh: ‘I don’t think that the flesh is necessarily treacherous, evil, bad. It is cantankerous, and it is independent. The idea of independence is the key. […] I notice that my characters talk about the flesh undergoing revolution at times’ (Rodley, 1996: 80)

The only way to survive in the monstrous, godless, unpredictable, vast sea full of monsters of the deep is to build a boat. The fragile sea vessel is the key metaphor for defining Jung’s character early in the film. Emma, who is afraid that her husband is losing interest in her because of all the pregnancies, gives Carl a pretty sailing boat. The film also abounds in images of lakes and oceans; Romantic trips with Sabina across Zürichsee shot from a bird’s eye angle, and various journeys by water including the famous grand trip to the United States. Jung, Cronenberg is trying to say, is like a vessel individuating against his passive will, being swayed by forces bigger than himself, small yet resilient, and bravely peering into the unfathomable depths. Jung believes in his ability to cross the River Styx in a small boat and come back intact.

The leaked contents, like the depths of the magnificent Zürichsee, are dangerous. Jung the hero, in his brave opening of the unconscious dam, gets inevitably contaminated. Or, as Cronenberg’s hero William Burroughs says in Naked Lunch, monsters have the habit of existing with ‘ominous snarls and mutterings’. Jung loses control. He has sex with a client. He is persuaded by the client to engage in certain sexual practices during which Keira Knigthley’s character, wearing white lace dresses, is sonorously spanked in recreation of her father’s brutal habits. Finally, Cronenberg’s protagonist reaches the verge of his human endurance and altogether starts losing his mind. The film ends with Jung being fragile and mentally unwell, placidly sitting on the bank of Lake Zurich (which metaphorically stands for Styx in the film), and looking into the distance. The scene renders the sense of disorientation and confusion in the face of an apparently meaningless and absurd world. While it echoes the real events, Cronenberg would not be interested in making a ‘sequel’ about the protagonist’s emergence out of the crisis. The director sees the unconscious as a wound that should remain open because his best monsters come out of it.

Bibliography:

Ratner, Megan (2012) ‘Interview with David Cronenberg’, Film Quarterly 66, 1: pages to be confirmed (it’s a forthcoming issue).

Rodley, Chris (1996) Cronenberg on Cronenberg, London: Faber and Faber.

Helena Bassil-Morozow PhD’s principal research interest is the dynamic between individual personality and socio-cultural systems in industrialised and post-industrial societies. She is an honorary research fellow of the Research Institute for Media Art and Design, University of Bedfordshire.Helena’s books include Tim Burton: the Monster and the Crowd (Routledge, 2010) and The Trickster in Contemporary Film (Routledge, 2011). Tim Burton discusses the themes of creativity, identity, nonconformity and individualism, which permeate all Burton’s films, in terms of postmodern alienation and plurality of the subject. TheTrickster in Contemporary Film examines the role of the trickster figure in cinematic narratives against the cultural imperatives of modernity and postmodernity, and argues that cinematic tricksters invariably reflect cultural shifts and upheavals.

Helena is currently working on two new Routledge projects, The Trickster in Society and Culture and Jungian Film Studies: the Essential Guide (the latter co-authored with Luke Hockley)”.

These books are available on our Online-Store, follow this link https://appliedjung.com/online-store and select the catagory “Post Jungian Books”.

Comment (1)

You need to take part in a contest for among the ideal blogs on the web. I will suggest this webpage!

michael kors crossbody bag