Systema munditotius: a Master Symbol

The question, “who am I?” lies at the heart of psychological and spiritual practice. It is the origin of self-inquiry. In Jungian psychology it is both the foundation stone and telos of individuation, the art of becoming oneself. The idea that there is indeed an answer to the question of one’s true nature is axiomatic to self-reflection and inquiry. Albeit that the answer is frequently maddeningly elusive and may lead the subject to either abandon the search or to be seduced by some form of deconstructive or apophatic strategy. It is, in other words, arguably, an unanswerable question. Simultaneously, however, one might argue that sans answer it is an unlivable life.

In the field of depth psychology, the creative genius and founder of analytical psychology[1], Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961), addresses this question in the Western philosophical tradition dating back to Plato. Jung’s opus, much of which directly addresses this question of authentic identity or the search for what Jung came to term “the Self”, stands out as an iconic intellectual and cultural achievement of the 20th century. Jung’s Collected Works number some 18-volumes[2] written over a lifetime of focused scholarly and empirical research in his practice as a psychologist, attending physician at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital[3], his extensive travels, close association with Sigmund Freud in the early days of psychoanalysis[4], his Eranos seminars[5] and his study of Eastern and Western mysticism.

Jung’s approach to this question of self-identity although multifaceted and layered is also remarkably consistent. I’ll attempt to explain this framing of self-identity as simply and succinctly as I can.

In essence Jung’s view was that the subject’s identity, or in Jungian parlance: the subject’s individuation, transcended the boundaries of the conscious ego identity to encompass the unconscious self, typically hidden from consciousness. “Typically,” i.e., for the most part. Not entirely however, otherwise a discourse between the two registers of psychological activity: conscious and unconscious, would be entirely impossible. As such, we might read the term “unconscious” as it is used in psychoanalysis, as relatively rather than completely unconscious.[6] The boundaries of conscious awareness can be extended to encompass portions of what was previously unconscious, thereby fertilising, and amplifying consciousness.

At the center of the personality, transcending both the conscious and unconscious aspects of the subject’s psychology is the Self. This Self, sometimes referred to as the ‘self-archetype’ is then the candidate and conceptual center of the subject’s identity and that toward which any serious inquiry as to the nature of one’s true identity is oriented. It is the telos of the question, “Who am I,” at least from the Jungian perspective.

The challenge and the virtue of psychology as a branch of philosophy[7], is its therapeutic focus or telos of therapeia.[8] In other words, psychologically speaking, simply providing a conceptual, rational and intellectual understanding of an idea is inadequate to the task of therapeia. In order for the subject’s soul or psyche to be recovered and redeemed it is necessary for the abstract idea to become a living reality in the subjects psyche. To use a current situation to illustrate the point, there is a difference between watching the war unfolding in the Ukraine from the comfort of one’s living room, or to be on the ground fighting the war there. Both aforementioned subjects “know” about the war in the Ukraine, but clearly not in the same sense.

In addition to the need to move from pure theoreia[9] to therapeia there is the not insignificant challenge in establishing a relationship between consciousness and the unconscious, or between the ego and the Self. The unconscious and the Self cannot be represented in consciousness in the same way conscious content can be. These terms, as I have attempted to explain, refer to something not directly knowable or conscious, i.e., un-conscious. To this effect and by way of addressing this issue, a monumental breakthrough Jung made for depth psychology was his reframing of symbols and the symbolic perspective that establishes or, more modestly, at least, amplifies, the epistemology of the unconscious. Jung situates symbols as a special and unique kind of signification, where symbols refer to something only partially known. Even if the limit of this partial knowledge is only the symbol itself, “as expressions of a content not yet consciously recognized or conceptually formulated.”[10]

These symbols can be universal or cultural in character. The way certain symbols have significant meaning for all human beings, symbols such as the sun and the ocean, as two obvious examples. Altenatively, symbols can be more personal, where some phenomenon, which is ordinary regarded as mundane or prosaic, takes on a numinous quality for the individual subject. That said, depth psychology demonstrates that even where a symbol has universal or mythological significance it also has a personal subjective dimension for the subject and the inverse, personal symbols also have a universal meaning. Both of these elements are important in understanding the significance of a symbol for the subject.

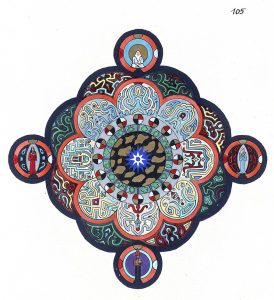

An example of this is the symbol of the mandala for Jung, which has a long cultural and archetypal history, and which also came to Jung as a personal intuition, and in both contexts symbolises the Self.

It is now to this symbol of the mandala and Jung’s interpretation of the symbol we turn for its capacity to further illuminate the inquiry into our essential nature or self-identity, and answer to the question, “who am I?”

The mandala as a symbol of the Self

The mandala was an important symbol for Jung, possibly his most important symbol. The word “mandala”, from the Sanskrit meaning literally “circle” has its origins in in the Hindu mystical tradition. That said, it represents something archetypal, i.e., universal, and instances of mandalas or magic-circles can be found across cultures and historical periods.[11]

The mandala was an important symbol for Jung, possibly his most important symbol. The word “mandala”, from the Sanskrit meaning literally “circle” has its origins in in the Hindu mystical tradition. That said, it represents something archetypal, i.e., universal, and instances of mandalas or magic-circles can be found across cultures and historical periods.[11]

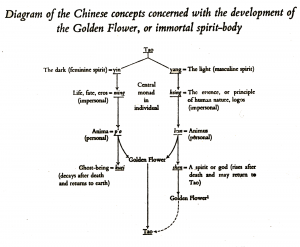

An especially significant example of this comes from Taoist alchemy and came to Jung when he received Richard Wilhelm’s translation of ‘The Secret of the Golden Flower’. Jung recognised in the microcosmic orbit meditation described in the text that is was an instance of the mandala symbol. Encountering this alchemical text was a breakthrough for Jung in his understanding of mandalas and also provided an independent precedence, which gave him the confidence to speak about his own research and experiences with mandalas.

“The text gave me an undreamed—of confirmation of my ideas about the mandala and the circumambulation of the center. This was the first event which broke through my isolation. I became aware of an affinity; I could establish ties with someone and something.”[12]

“Our text promises to ‘reveal the secret of the Golden Flower of the great One’. The Golden Flower is the light, and the light of heaven is the Tao. The Golden Flower is a mandala symbol which I have often met with in the material brought me by my patients. It is drawn either seen from above as a regular geometric ornament, or as a blossom growing from a plant. …The ‘enclosure’, or circumambulatio, is expressed in our text by the idea of a ‘circulation’. The ‘circulation’ is not merely motion in a circle, but means, on the one hand, the marking off of the sacred precinct, and, on the other, fixation and concentration.”[13]

“The union of opposites on a higher level of consciousness is not a rational thing, nor is it a matter of will; it is a psychic process of development which expresses itself in symbols. Historically, this process has always been represented in symbols, and today the development of individual personality still presents itself in symbolical figures. This fact was revealed to me in the following observations. The spontaneous fantasy products we mentioned above become more profound and concentrate themselves gradually around abstract structures which apparently represent principles’, true Gnostic archai. When the fantasies are chiefly expressed in thoughts, the results are intuitive formulations of dimly felt laws or principles, which at first tend to be dramatized or personified. (We shall come back to these again later.) If the fantasies are expressed in drawings, symbols appear which are chiefly of the so-called mandala type. ‘Mandala’ means a circle, more especially a magic circle, and this symbol is not only to be found all through the East but also among us.”[14]

“The union of opposites on a higher level of consciousness is not a rational thing, nor is it a matter of will; it is a psychic process of development which expresses itself in symbols. Historically, this process has always been represented in symbols, and today the development of individual personality still presents itself in symbolical figures. This fact was revealed to me in the following observations. The spontaneous fantasy products we mentioned above become more profound and concentrate themselves gradually around abstract structures which apparently represent principles’, true Gnostic archai. When the fantasies are chiefly expressed in thoughts, the results are intuitive formulations of dimly felt laws or principles, which at first tend to be dramatized or personified. (We shall come back to these again later.) If the fantasies are expressed in drawings, symbols appear which are chiefly of the so-called mandala type. ‘Mandala’ means a circle, more especially a magic circle, and this symbol is not only to be found all through the East but also among us.”[14]

Mandalas feature prominently in Jung’s visions, captured in the mystical text Liber Novus.

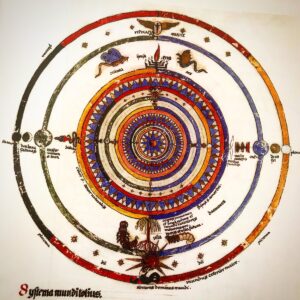

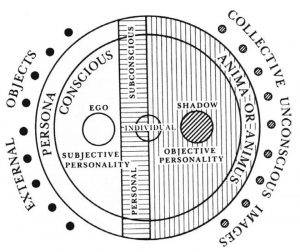

Jung’s first, and possibly most important mandala, that he termed “Systema Munditotius” , drawn in 1916 and related to his visionary experiences of that time described in Sermones ad Mortuos (Seven Sermons to the Dead). The mandala is a accompanied by some explanatory notes.

We see an earlier draft of the Systema Munditotius in Jung’s personal journals, later published as The Black Books. ( Black Book 5, page 169) In this draft Jung adds an icon legend to the mandala.

The symbol of the mandala is also apparent in this early modelling of the psyche from a lecture Jung gave in 1925, and has become an iconic model of the psyche by Jung.

After many years of fascination with and drawing mandalas Jung had what we can call a big dream that occurred around the time of his receiving the Secret of the Golden Flower,

“I found myself in a dirty, sooty city. It was night, and winter, and dark, and raining. I was in Liverpool. With a number of Swiss—say half a dozen. I walked through the dark streets. I had the feeling that there we were coming from the harbour, and that the real city was actually up above, on the cliffs. We climbed up there. It reminded me of Basel, where the market is down below and then you go up through the Totengasschen (Alley of the Dead), which leads to a plateau above and so to the Petersplatz and the Peterskirche. When we reached the plateau, we found a broad square dimly illuminated by streetlights, into which many streets converged. The various quarters of the city were arranged radially around the square. In the center was a round pool, and in the middle of it a small island. While everything round about was obscured by rain, fog, smoke and dimly lit darkness, the little island blazed with sunlight. On it stood a single tree, a magnolia, in a shower of reddish blossoms. It was as though the tree stood in the sunlight and were at the same time the source of light. My companions commented on the abominable weather, and obviously did not see the tree. They spoke of another Swiss who was living in Liverpool and expressed surprise that he should have settled here. I was carried away by the beauty of the flowering tree and the sunlit island, and thought, “I know very well why he has settled here.” Then I awoke.

Jung comments:

On one detail of the dream, I must add a supplementary comment: the individual quarters of the dream were themselves arranged radially around a central point. This point found a small open square illuminated by a larger streetlamp, and constituted a small replica of the island. I knew that the “other Swiss” lived on the vicinity of one of those secondary centres.

The dream represented my situation at the time. I can still see the grayish-yellow raincoats, glistening with the wetness of the rain. Everything was extremely unpleasant, black and opaque – just as I felt then. But I had a vision of unearthly beauty, and that is why I was able to live at all. Liverpool is the “pool of life.” The “liver,” according to an old view, is the seat of life, that which makes to live.”

This dream brought with it a sense of finality. I saw that here the goal had been revealed. One could not go beyond the centre. The centre is the goal and everything is directed towards that centre. Through this dream I understood that the self is a principle and archetype of orientation and meaning. Therein lies its healing function. For me, this insight signified an approach to the center and therefore to the goal. Out of it emerged a first inkling of my personal myth.

After this dream I gave up drawing or painting mandalas. The dream depicted the climax of the whole process of development.”[15]

Jung pursued this question and goal his entire life. As he put it, “My life has been permeated and held together by one idea and one goal: namely to penetrate into the secret of the personality. Everything can be explained from this central point and all my works relate to this one theme.” (MDR, p. 206)

It is with the symbol of the mandala that Jung seems to get closest to a a satisfactory answer.

Later in MDR, Jung goes on to say,

“More than twenty years earlier (in 1918), in the course of my investigations of the collective unconscious, I discovered the presence of an apparently universal symbol of a similar type—the mandala symbol. To make sure of my case, I spent more than a decade amassing additional data, before announcing my discovery for the first time. The mandala is an archetypal image whose occurrence is attested throughout the ages. It signifies the wholeness of the self. This circular image represents the wholeness of the psychic ground or, to put it in mythic terms, the divinity incarnate in man.” [16]

Jung describes the mandala as “Formation, Transformation, Eternal Mind’s eternal recreation. And that is the self, the wholeness of the personality”[17] In the mandala the opposites are united, and the Self is symbolically represented.[18] In the centre of the mandala the Self is represented, “One could not go beyond the centre.”

With the symbol of the mandala Jung provides us with a way of signifying (representing) the answer to the question “who am I?” This answer is symbolic, which is the only way a meaningful and truthful answer can be provided to this question.

To experience the psychic and spiritual gravitas of this symbol it needs to be engaged with and experienced. Merely understanding it as an intellectual concept is inadequate to experiencing its archetypal and symbolic impact. To put this another way, you need to work with the symbol of the mandala yourself in order to understand its impact and be transformed by it.

To provide you with a prescription for doing this here would be an injustice to the concept and would reduce this profound idea and symbol to a prosaic and limited method of practice. What I can say though is the mandala is a type of master signifier and master symbol. It is a meta-symbol and is able within the radius of a single circle encompass the “system of the whole (world/cosmos)” which is exactly what Jung does with Systema munditotius in 1916. It is a symbolisation of the prevailing psyhco-cosmology. Suffice to say, beyond the various esoteric and spiritual practices that utilise this symbol, which are myriad, there is nothing stopping you from finding your own way into the magic circle. Jung blazed a trail to a real and meaningful answer to this profound existential question and illuminated a way which we can follow, amplify, be guided or simply inspired by.

Until we speak again,

Stephen.

References

[1] More commonly referred to simply as “Jungian Psychology”.

[2] Excluding the general index and bibliography as part of the Collected Works, and then the additional Red and Black Books, letters, Memories Dreams Reflections, and various published Seminars.

[3] 1900 and 1909

[4] 1907 to 1913

[5] 1933 to 1943

[6] Possibly arguing for the idea that the term “sub-conscious” largely relegated to the scrap heap of redundant signifiers, was unwisely so relegated. Its downfall is its structural connotation, situating the unconscious as a basement area to the conscious mind, which proves an unhelpful and very limiting way to conceive of the unconscious, which, research in the field suggests, is a much more significant aspect of the psyche pre-dating and transcending the more limited function of consciousness. Nevertheless, what is missing in the replacement of “sub-conscious” by “unconscious” is the denotation of an area neither fully conscious or unconscious, but in a liminal register, able to move between the two.

[7] My framing, psychology although including elements of and being influenced by philosophy is not usually conceived of as branch of philosophy.

[8] care, attention, healing

[9] Contemplation

[10] CW16 ¶ 339. For more on symbols https://appliedjung.com/symptom-or-symbol/ and https://appliedjung.com/man-and-his-symbols-synopsis/

[11] A mandala (Sanskrit: मण्डल, romanized: maṇḍala, lit. ’circle’, [ˈmɐɳɖɐlɐ]) is a geometric configuration of symbols. In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of practitioners and adepts, as a spiritual guidance tool, for establishing a sacred space and as an aid to meditation and trance induction. In the Eastern religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Shintoism it is used as a map representing deities, or especially in the case of Shintoism, paradises, kami or actual shrines. A mandala generally represents the spiritual journey, starting from outside to the inner core, through layers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mandala

[12] C. G. Jung, ‘Memories, Dreams, Reflections’, (1961/1989) (p. 197)

[13] From Jung’s commentary on ‘The secret of the Golden Flower’

[14] Ibid

[15] Jung, C. G., ‘Memories, Dreams and Reflections’, (1961/1989) page 223

[16] Ibid, p. 335

[17] Ibid, p. 196

[18] Laughlin, K. (http://kqlaughlin.com/blog/the-mandala/ )

Comments (18)

Hi Stephen, I am a Ph.D. student at the University of Pretoria and would like to cite the article above.

Could you perhaps send me your entire paper that discusses the restoration of self, as touched on in your article?

Kind regards,

Karien

Hi Karien, the paper is still being written, so I don’t have a copy to send you at the moment. You are welcome to cite this article.

I have been studying Jung and “playing around” with symbols and symbolic ritual work for three decades and this piece is a beautifully succinct description of my personal understanding of Jungian psychology. I intend to share this with friends to explain the ideas I often fail to illuminate clearly. I am thankful to you Stephen for writing and publishing this grounded explanation.

Thank you Sherryl, I’m really pleased it is of some value to you and hope it will be helpful in your continuing work.

Hi Stephen,

Just wanted to add my thanks for your presentation here. For years I feel like I have read “around the edges” (perhaps of the circle…lol) but you have so succinctly put the pieces together for me that I have much clearer picture of the whole than I did before! I knew of the Liverpool dream, Jung’s interest in mandalas (I’ve actually led workshops on creating mandalas), and Jung’s synchronistic connection to Wilhelm’s The Secret of the Golden Flower….but never had the threads to connect them as you have! Thanks again for your work! All the best!

Thank you in turn Nancy. Without intending false modesty, I was in very much the same state with respect to these diverse but related threads and themes until very recently. I have been teaching and leading process work based on the Secret of the Golden Flower for close to two decades now. This year I had a breakthrough where for the first time the character of the circumambulation of the microcosmic orbit as a mandala – notwithstanding the fact that Jung emphasises this so heavily in his commentary on the text, really landed for me. That and I had the good fortune to come across a post from a colleague, Kiley Laughlin, speaking about Systema munditotius – and his getting to see the original sketch at Kusnacht!

Somehow in this process, a synthesis occurred wherein I was able to see how these diverse threads connected. I have also had the very good fortune of being able to work practically on this with a group of students this year, which of course, has also been immeasurably helpful in deepening my own understanding of the symbolic significance of the mandala.

Hello Stephen,

The first thing that struck me about your essay was your focus on WHO AM I. This is also the question that Sri Ramana Maharshi urged us all to address. His method of Self Enquiry (Atma Vichara) entails working one’s way back to the root thought “I “. If you can do this and ground yourself in the “I” thought you realize that man is God and God is man.

When Jung was in India he could have visited Sri Ramana. In fact Heinrich Zimmer urged him to do so. But he did not and he said that even if he could go back to India he would have made the same decision. He explained his reasons in his Preface to Zimmer’s Holy Men of India which is at the end of CW11. I find this very unsatisfactory – what do you think?

Peace,

Fred

Fred, yes, I’m aware of Jung’s resistance to meeting Sri Ramana Maharshi. And I certainly understand you finding his stated reasons unsatisfactory. Its seems as we were cheated out of a historic encounter and would have been that much richer for their having met.

That said, I’m not entirely unsympathetic to Jung for resisting to meet with Maharshi. On one hand I think it was a form of narcissistic inflation, that prevented him from seeing Maharshi. On the other hand, I think Jung managed to light a flame in the darkness of the inner world for Western Man, one that may not have withstood an encounter with a tradition as ancient, well-grounded and evolved as carried in the Indian mystical and yogic tradition. I think Jung was acutely aware of and sensitive to the fragility of what he had discovered and was striving to protect its integrity. Anyway, who’s to say, that the myth he sought to perpetuate, and I’ve accepted it. It could be BS, maybe he simply had gippo guts (which I believe he did) and wasn’t up to the encounter. Whatever the reasons, one must bemoan the lost opportunity.

Perhaps, Jung wanted to make a statement that it’s possible for a westerner to become enlightened. He did not have any unanswered or burning questions he hasn’t explored and neither did Jung needed to seek anything outward. He exploded in depth the question “Who am I?” and there was a possibility of not being moved from inside to make the meeting happen. There is also another way of meeting-the meeting of the souls when space and words are not needed. The energy exchange happens between kindred spirits.

It is worth noting that Meher Baba (1894-1969) said there is only one question, “Who am I” and only one answer, “I am God”; yet in between the question and the answer is the long evolutionary journey. You may be interested to read his treatises on the ego and its dissolution in his Discourses which were written almost 100 years ago. He also said that “when the unconscious becomes fully conscious, God-realization occurs.”

Hello Stephen,

I am so delighted to come upon your very special and insightful article. I like others here have been floundering in the midst of many years of analysis and study to pinpoint some of Jung’s ideas that you have been able to put into perspective so well. Many thanks.

Thank you Joan, I’m delighted you found it a worthwhile read. I hope to do much more on the topic, one which is so rich for further exploration, in good time.

Thanks so much for this article. I’m on the SGF course and this article has pulled together all the work on the Mandala we’ve been doing. I’ve engaged faithfully with all the Mandala activities without really seeing how everything is linked. When I read your article, in a mysterious way, things have fallen into place! Now I can revisit the applications with new eyes. Thanks again.

Wonderful Annie, so very pleased to hear this

Stephen, this is wonderful! I had previously missed some of the quotes you include here.

Thank you!

PS: Is it all right to share this outside of CAJS forums?

xox

Glad you found it useful Max. Yes, certainly its okay to share, once I publish it here, its in the public domain.

Thank you Stephen for this write-up. I think the archetypal image of the mandala is truly encompassing in the sense that it may symbolize the world we live in and the world embedded in us. I mean that,the mandala can stand for planet Earth in the Solar system,i. e. the world out there and our body as a physical, biological and psychological system,i.e., the world in here. Of course,this is just a perspective of a broad view that can still be further explored.

Thank you Stephen. I found your blog most intriguing and interesting as well as the comment by Ann Haug since “I am God” is the answer of the Hindu tradition to the question of human identity. I have been connected to an Ashram for several years and I find it difficult to “connect the dots in my own mind” so to speak of that clearcut simple idea-concept-conviction and the scientific positivistic analytical approach to the exploration of the psyche. In reading Jung I have always had the feeling that he is on the verge of jumping into the spiritual. The fact that his personal Red Book took so long to be published attests to the fact that he applied his findings to himself but his heirs were wary of making this known publicly. Not meeting with an Hindu Guru also shows that reluctance. Fortunately the scientific atmosphere itself is changing quite a bit and perhaps, eventually, the radical answer of the Hindu tradition will be understood and accepted in an authentic sense by Western thought and culture. I suspect there is a lot to do along those lines.