The Interpretation of Fairy Tales

This following article is an overview of Marie-Louise von Franz’s 1970 book The Interpretation of Fairy Tales.

The interpretation of fairy tales is a wonderful opportunity to exercise the craft of dream interpretation, for dreams possess the quality of always producing new information unknown to both the dreamer and the analyst, such that they should be dealt with as objectively as possible. In analysis or one’s personal interpretation, knowledge of the conscious situation surrounding the dreamer may hinder our objectivity and may even facilitate a reliance on this information to inform our interpretation, ultimately weakening our command of the craft. Fairy tales, which are not connected to any individual, offer us the opportunity to exercise objectivity.

It should be noted, however, that fairy tales differ from dreams in that they are not products of the personal unconscious but rather the collective unconscious and thus speak to archetypal experiences. Therefore, one mustn’t interpret the hero or heroine of a fairy tale from a personalistic point of view, for their characters represent structures of a psyche working toward individuation. Specifically, all fairy tales work to describe the Self. The Self is both the psychological totality of the individual and the regulating center of the collective unconscious, and each fairy tale describes a different phase (e.g., the beginning stage) or may focus on a specific archetypal element (e.g., the shadow) of this experience of the Self.

“Fairy tales are the purest and simplest expression of collective unconscious psychic processes. Therefore, their value for the scientific investigation of the unconscious exceeds that of all other material. They represent the archetypes in their simplest, barest, and most concise form. In this pure form, the archetypal images afford us the best clues to the collective psyche. In myths or legends, or any other more elaborate mythological material, we get at the basic patterns of the human psyche through an overlay of cultural material. But in fairy tales there is much less specific conscious cultural material, and therefore they mirror the basic pattern of the psyche more clearly.”

―

A Brief History of Fairy Tales:

Until the 18th century, fairy tales were told to both children and adults and possessed great integrity, representing “the philosophy of the spinning wheel (Rockenphilosophie).” (ibid) The collection and release of fairy tales published by the Brothers Grimm in the 19th century sparked international interest in the collection of national folklore. Von Franz tells us that, “At once, everybody was struck by the enormous number of recurrent themes . . . in French, Russian, Finnish, and Italian collections.” (ibid)

Thereafter, many schools of thought (historical, scientific, religious, literary etc.) exploring the wisdom, parallels and recurrent motifs of fairy tales flourished. Ludwig Laistner, for example, proposed that folktales derived from common dream material. Around the same time, Karl von der Steinen backed this theory by explaining how indigenous people’s relationship to their dreams informed their supernatural beliefs It was also during this period that Adolf Bastian theorised that all basic mythological motifs are elementary thoughts that do not migrate but are rather innate, born from within the individual. This is in line with Jung’s conception of the archetype as “the structural basic disposition to produce certain mythologem, the specific form in which it takes shape being the archetypal image”. (ibid) However, archetypes are not only elementary thoughts but also elementary poetical images, fantasies, emotions or even impulses toward action that cannot be viewed from a purely intellectual standpoint, for the emotional experience attached to an archetype is an essential component of its structure. Its feeling value is what gives it life. Unlike the other sciences, psychology, and by extension our exploration of fairy tales, cannot afford to overlook the feeling tone, for humans are the basis, the soil, from which the symbolic motifs grow.

Von Franz is of the opinion that fairy tales originate from an invasion by the collective unconscious in the form of a dream or waking hallucinations, “whereby an archetypal content breaks into an individual life” (ibid) and therefore collective consciousness. Through gossip the archetypal content is enriched and produces a local saga, and those memorable enough are condensed and crystallised until they attain the universal status of the fairy tale. What is manifest in the collective unconscious of mankind, what archetypal content is of importance to the time, will centralize and become amplified, and because fairy tales speak to the most basic structures of the human psyche and therefore possess universal significance, will transcend racial, cultural and linguistic boundaries.

A Method of Psychological Interpretation:

The argument has been made by specialists of mythology that fairy tales speak for themselves, and that the process of interpretation is just replacing one myth for another, the Jungian myth, to which von Franz responds:

“We are aware of the possibility and know that our interpretations are relative, that they are not absolutely true. But we interpret for the same reason as that for which fairy tales and myths are told: because it has a vivifying effect and gives a satisfactory reaction and brings one into peace with ones unconscious instinctive substratum, just as the telling of fairy tales always did. Psychological interpretation is our way of telling stories; we still have the same need and we still crave the renewal that comes from understanding archetypal images. We know quite well that it is just our myth.”

―

So, how does one begin to interpret the meaning of a fairy tale?

The process of interpretation can be dealt with in two parts. The first is an examination of the central components of the archetypal tale, and the second is the amplification of its core symbols.

The Four Central Components:

The exposition: the time and space of the drama. Often fairy tales will begin in the realm of the collective unconscious, that is, ‘Once upon a time’ or what “most mythologists now call the illud tempus, that timeless eternity, now and ever”. (ibid)

The dramatis personae: the characters involved. It is important to examine the numerical and gendered patterns of the characters, and how these shifts throughout the story. Identify the central problem facing the characters within the story and whether this problem is resolved by the end, as this will tell you something of the psyche’s progression toward individuation.

The peripeteia: the movement of the story, its ups and downs, and finally,

The lysis: the gradual closing of the tale. Is the ending positive or negative?

Amplification of the Symbols:

Once this structure is established, we can begin amplifying the symbols. According to von Franz, “amplification means enlarging through collecting a quantity of parallels”. (ibid) In other words, methodically working through and amplifying each symbol and motif by examining them against in a wide variety of comparative literature. Von Franz gives the example of a mouse. “For instance, you have read that mice represent the souls of the dead, witches, that they are bringers of the plague, and they are also soul animals because when someone dies, a mouse comes out of his corpse, or he appears as a mouse, and so on.” (ibid)

Then, you can see which of these amplifications fit your motif within the context of your story. Some may while others do not. Do not disregard those amplifications which do not fit, but rather keep them close at hand, until you have moved through the entirety of your tale.

Finally, the interpretation itself requires our translation of the amplified story into psychological language. For example, the hero who overcomes the terrible mother as a psychic process would be described as follows: “the inertia of unconsciousness is overcome by an impulse toward a higher level of consciousness.” (ibid) For only then will the interpretation make sense.

A Tale and its Interpretation:

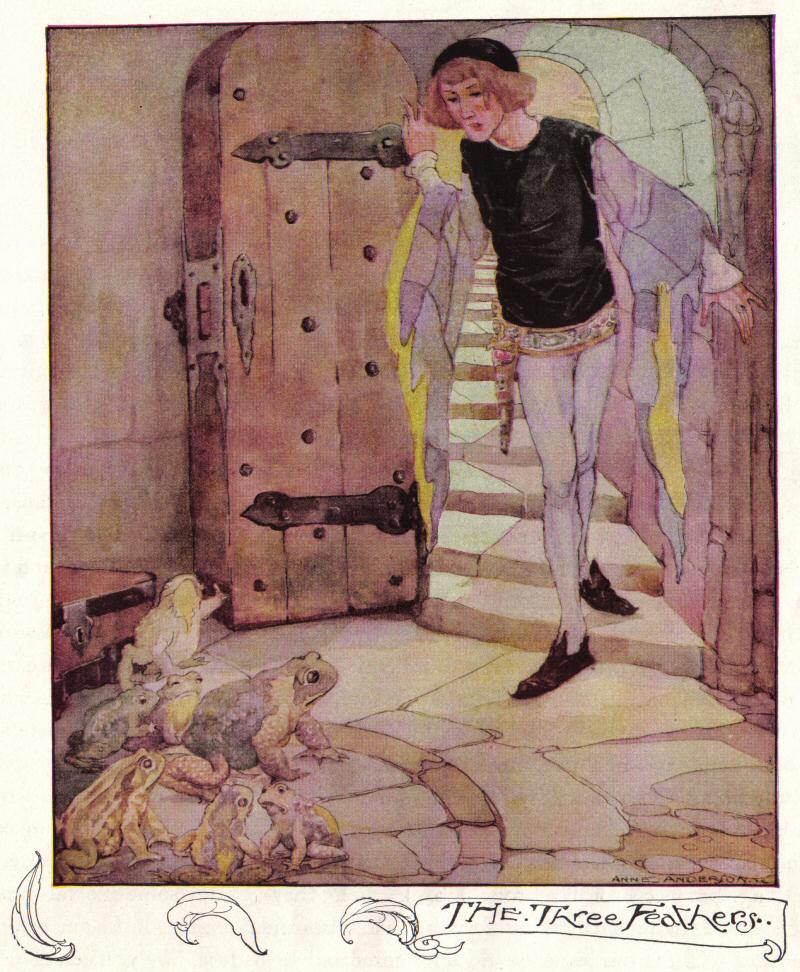

Von Franz analyses several fairytales, most extensively The Three Feathers by the Brothers Grimm, to illustrate her theory. I will provide a brief overview of the tale and her interpretation below.

A king has three sons of which one must become heir. He casts three feathers into the air and sets them three challenges, each must follow their individual feather and bring home the most beautiful carpet, the most beautiful ring, and finally, the most beautiful bride. The youngest of the three, Dummling, called so because he is thought to be the most dim-witted, follows his feather to a trap door that descends into the earth, where-upon he meets a magical toad who helps him win each of the three challenges in succession. His bride is a toad who turns into a beautiful woman upon her entrance into a carrot vehicle. Due to the protests of his older brothers, the boys are set a final challenge, in which whoever of their wives is able to jump perfectly through a ring shall acquire the throne. Dummling’s toad-turned-bride performs the trick perfectly, and so Dummling is crowned heir, and rules over the kingdom in wisdom.

Here we have a story centered around the redemption of the feminine principle. This is made evident by the absence of the feminine (i.e., the queen mother) at the start of the tale, and the inheritance of the kingdom’s dependence on finding and marrying the right wife, which brings resolution to the tale. It is also shown by the aid of the feminine element throughout, for the magical toad helps Dummling win all his challenges, and it is his wife who succeed at winning the final challenge.

The king is the symbol of the Self – the Self as the dominant collective-conscious attitude of the society in which the tale was produced, as well as the regulating center of the psyche – who is in danger of petrification should he not find some sense of renewed contact with the unconscious. The absent queen is that accompanying feminine element required for such relatedness to the unconscious, to prevent sterility or inertia. “We must assume, therefore, that the story has to do with the problem of a dominant collective attitude in which the principle of Eros – of relatedness to the unconscious, to the irrational, the feminine – has been lost.” (ibid)

The motif of the male quaternion alludes to the four functions. The king is the main function, the two ‘clever’ boys represent the auxiliary functions, and Dummling represents the basis for building up the inferior function. Dummling is also the hero of the story, for he is tasked with renewing the life principle and resorting a healthy, conscious situation. That is, the hero presents the model of an ego functioning in accordance with the requirements with the Self. It our tale, Dummling is not stupid but in fact spontaneous and naïve, and for this reason is able to access a renewed conscious attitude capable of contacting the feminine.

Dummling’s feather (a symbol of inspiration from the unconscious) requires him to descend into the depths of Mother Earth, whose internal structure (as opposed to virginal nature) alludes to traces of a former civilization in which the feminine element was once present but has since been repressed. There he meets a toad, who, through the process of amplification we come to find represents the maternal womb, the mother, and the earth goddess who can bring life or poison it, containing within herself all those elements lacking in the conscious setup of our tale. Moreover, our hero finds her surrounded by a ring of little toads at the entrance of her underground home, which shows us that “together with the feminine, the symbol of totality is constellated.” (ibid)

The carpet is the purpose and patterns of one’s individual life, the secret design of fate. The ring is a symbol of totality and connectedness, its golden colour symbolic of the eternal and divine, and its precious gems our closely held psychological values. Therefore, we might say the ring represents the eternal connectedness to the divine and consciously chosen obligation toward the Self. The transformation of our toad into a beautiful woman speaks to the anima, a man’s connection to the unconscious. In an alternative version of the tale, the toad is redeemed through trust, acceptance and love, and in our tale, by way of entering a carrot vehicle. The carrot is a somewhat erotic vegetable and so may well represent sexual fantasies as means bringing Eros into consciousness.

“When Dummling brings together the young toad and the vehicle, then the toad turns into a beautiful woman. This would mean, practically, the that if a man has the patience, and the courage to accept and bring to light his nocturnal sex fantasies, to look at what they carry and to let them continue, developing them and writing them down (which allows for further amplification), then his whole anima will come to light.”

―

The final test, in which Dummling’s bride jumps through the ring, alludes to finding the inner center of the personality. By hovering midair, one essentially leaves earth to go inward. It is the need to remain loyal to the inner reality of the anima that is expressed in her jumping through the ring.

The anima is the guide to restoring a rich symbolic life. A problem with assimilating the anima will prevent a man from living in tune with his inner rhythm. Courage and naivety are needed to convert this rational consciousness to the symbolic life, which enriches and makes life meaningful, for it requires a gesture of generous acceptance and a sacrifice of the intellectual and rational attitude.

I will leave you with the following quote from von Franz,

“Healing has really taken place only when there is a constant state of relationship between consciousness and the unconscious . . . when a condition of continual relationship with the other side has been established.” (ibid)

Art: The Three Feathers by Anne Anderson

Comments (7)

Very interesting! I’m reading old Russian fairy tales at the moment as well as ghostly Japanese folklore. So there is perhaps another element during interpretation to fathom that a leading character (or any character) doesn’t have to be a person, beast, fairy, hero; but can be the collective consciousness written at a prominent time and place in history so potent that it’s traditions, rituals and philosophy resonate strongly throughout the story. The state of mind and the writers intent, albeit politically motivated or simply a jilted wife. A story and it’s history and heritage are important in deciphering fairy tales. Let’s call them the fairytale’s tale.

Well said!

Thank you Kiva for this highly engaged and researched reading. Thank you also for leaving us with the quote from von Franz,

“Healing has really taken place only when there is a constant state of relationship between consciousness and the unconscious . . . when a condition of continual relationship with the other side has been established.” (ibid)

In a way, this is what I experience in the relationship with my husband, it is as if I have a complete understanding of each other. However, we needed to work it all through in order to get where we are now.

I love the way the ‘hero’ figure is so often, by the standards of his (our) society, inferior, even unfinished/incomplete by virtue of his stature (often ‘Little’), youth etc. Whereas his brothers/rivals are finished, complete, so closed to change.

Very lovely and timely for me. Thank you very much. As I am in the midst of The Sacred Marriage course and currently working with anima and animus, your article brings rich symbolism to my own process of which I am becoming more conscious.

That’s wonderful to hear.

I find it super that after years the importance of fairy tales is getting attention again.

In my psychological course (The fairytale trail) that I offer, I take my clients through amplification path also along the fairy tales.

Keep up the good work!